Reliability Metrics That Actually Matter

The handful of reliability metrics that predict churn, trust, and renewals—and how to instrument them.

Reliability Metrics That Actually Matter

Most teams drown in dashboards and still miss the signals that predict churn.

I've seen engineering teams with 47 Grafana dashboards, 200+ alerts, and no idea whether customers are happy or about to leave. The dashboards show CPU utilization and memory pressure and garbage collection pauses. They don't show whether the business is working.

Over twenty years running Conductor, we learned which metrics actually predicted renewals, which predicted churn, and which were noise dressed up as data.

Here's the handful of metrics that matter and how to instrument them.

Start with Business SLOs, Not CPU Charts

The most important mindset shift: measure what customers experience, not what servers experience.

Service Level Objectives (SLOs) are the promises you make to customers about performance. They're expressed in terms customers care about:

- "Scores posted within 15 minutes of receipt"

- "Registrations processed within 60 seconds"

- "Voucher reconciliation completed before 6 a.m. daily"

Notice what's missing: CPU utilization, memory usage, pod restarts, disk I/O. Customers don't care about those. Customers care about outcomes.

Why this matters:

System metrics are leading indicators at best. A CPU spike might predict a problem. A pod restart might cause a problem. But customers don't experience CPU spikes. They experience delayed registrations, missing scores, failed payments.

When you measure business outcomes, you're measuring what determines contract renewals and customer trust.

How to implement:

- Identify the 3-5 most critical customer outcomes (the things mentioned in contracts, the things that trigger support calls)

- Define measurable targets for each (not "fast" but "within X seconds")

- Map each business SLO to system metrics that explain performance

- Build dashboards that show business outcomes first, system metrics as drill-downs

Error Budget as a Scheduling Tool

Error budget turns reliability into a resource you spend, not a virtue you pursue.

The math:

If your SLO is 99.9% availability over 30 days, you have ~43 minutes of "budget" per month. That's 43 minutes of downtime, degradation, or failures before you've broken your promise.

Burn rate measures how fast you're consuming budget. A burn rate of 1.0 means you're using budget at exactly the sustainable pace. Above 1.0, you're heading for breach. Below 1.0, you have margin.

How to use it:

When burn rate exceeds threshold (we used 2.0), feature work pauses and reliability work enters the sprint. Not as a discussion—as a rule.

This removes the endless debate about "can we afford to work on reliability this sprint?" The burn rate tells you. If you're burning budget too fast, you work on reliability. If you have margin, you ship features.

The payoff:

Fewer surprise outages because reliability work is scheduled, not optional. Teams don't have to argue for "tech debt" time—the budget math creates it automatically.

In 2018, we had a month where burn rate hit 3.5 early. Feature work stopped. We fixed three underlying issues. Burn rate dropped to 0.4. The next month, we shipped features again. No heroics. Just math.

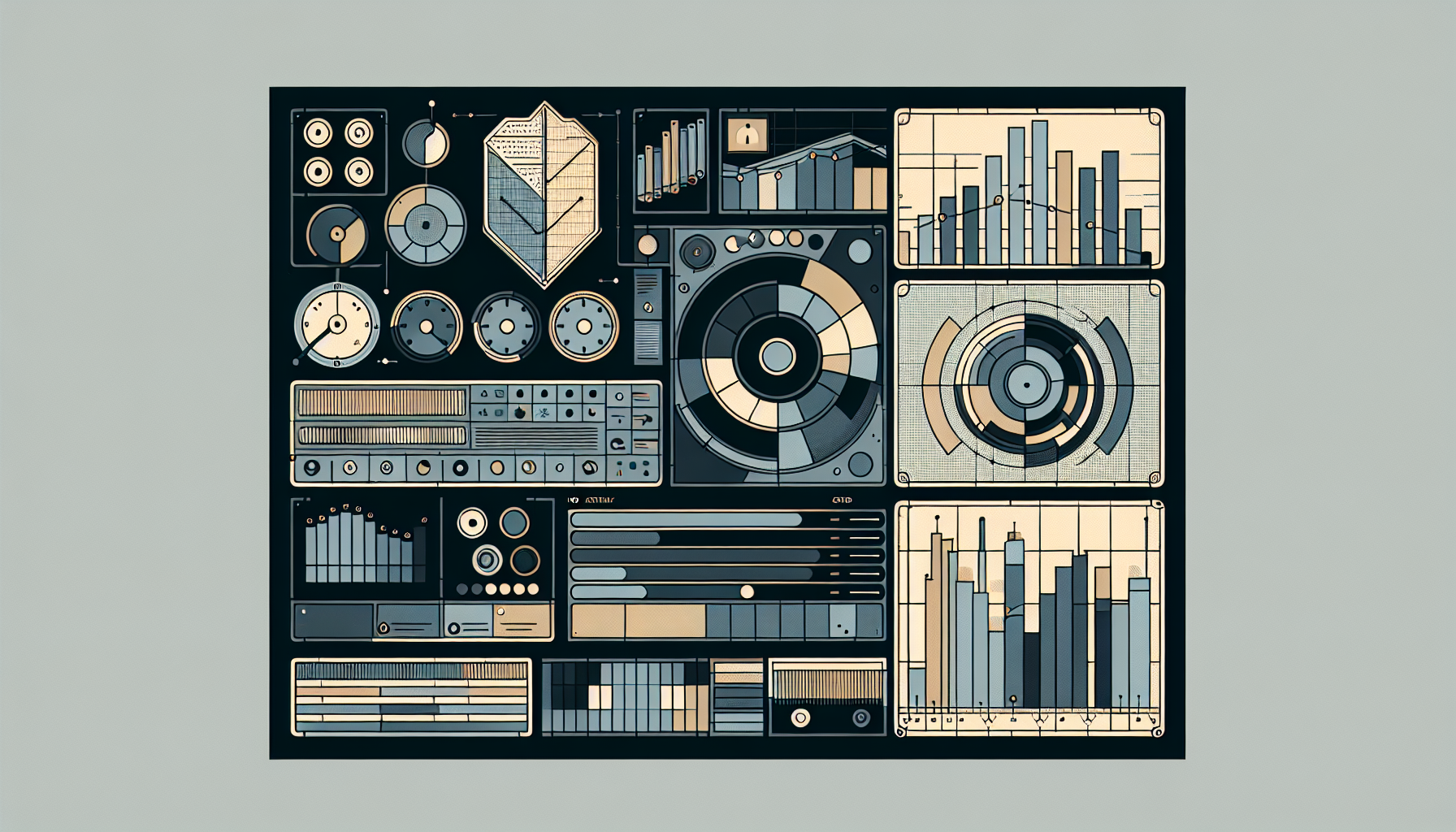

Signal Layers: Metrics, Logs, Traces

Different questions need different tools. Don't try to answer forensic questions with trend metrics.

Metrics for trends:

- Request rates and error rates over time

- Latency percentiles (p50, p95, p99)

- Queue depth and age

- Circuit breaker trip counts

Metrics answer: "Is the system getting better or worse? Are we meeting our targets?"

Logs for forensics:

- Structured logs (JSON, not prose) with consistent field names

- Correlation IDs that tie requests together across services

- Business entity IDs (customer ID, registration ID, transaction ID) in every log line

Logs answer: "What happened to this specific request? Why did this customer see an error?"

Traces for weirdness:

- Distributed tracing across multi-service requests

- Sampling on complex flows (the ones that touch many services)

- Trace IDs linked to logs and metrics

Traces answer: "Why did this transaction take 10x longer than normal? Where did the time go?"

No single layer owns truth. Metrics tell you there's a problem. Logs tell you what happened. Traces tell you where the time went. You need all three.

Leading Indicators to Watch

Some metrics predict problems before customers notice. Watch these:

Queue depth and age:

Rising queue depth means work is accumulating faster than it's processing. That's mildly concerning.

Rising queue age—the time the oldest item has been waiting—means user-visible lag is coming. That's urgent.

Alert on age, not just depth. A queue with 1,000 items processed in 10 seconds is fine. A queue with 100 items where the oldest is 30 minutes old is a crisis.

Circuit breaker trip counts:

Circuit breakers (patterns that stop calling failing services) should trip rarely. A sudden increase in trips signals:

- Partner issues (their API is degrading)

- Internal regressions (your code is generating bad requests)

- Network problems (connectivity is unstable)

Track trips over time. A baseline of 2-3 trips per day is different from 50 trips in an hour.

Backfill and reconciliation lag:

If nightly reconciliations start slipping—finishing at 7 a.m. instead of 6 a.m.—revenue reporting and compliance are next.

Reconciliation timing is a canary. When it degrades, something upstream has changed.

Manual override frequency:

A spike in manual overrides means automation isn't handling edge cases. Each override is a signal that something in the system isn't working as designed.

Track override frequency over time. Rising numbers mean you're accumulating automation debt that will eventually break trust.

Health Dashboards Executives Actually Read

Most dashboards are built by engineers for engineers. Executives won't read them, and shouldn't have to.

The three-pane structure:

Top pane: Business SLOs

Green/yellow/red indicators for each SLO with current burn rate. No numbers unless something is yellow or red. Executives should see green and move on.

- ✅ Registrations: 99.94% (target: 99.9%)

- ✅ Score posting: 99.97% (target: 99.5%)

- ⚠️ Reconciliation: 98.7% (target: 99.0%)

Middle pane: Current incidents

Active incidents with:

- Plain-language impact ("Registrations delayed ~5 minutes")

- Status (investigating / mitigating / resolved)

- Next update time (not "soon"—a specific time)

If there are no incidents, this pane is empty. Empty is good.

Bottom pane: Upcoming risks

Scheduled changes that could affect reliability:

- Deploys with risk ratings

- Vendor maintenance windows

- Migration milestones

Each item has an owner. If something goes wrong, executives know who to ask.

The payoff:

Executives stay informed without translating engineering graphs. They see three colors, a status, and upcoming risks. When they have questions, they know who owns each area.

Instrumentation Quick Wins

You don't need months of infrastructure work to get useful signals. Here's what you can do quickly:

Correlation IDs everywhere:

Generate a unique ID at the edge (the first service that receives a request). Pass it through every service, every log line, every external call.

Include tenant ID and business entity ID in the correlation ID format: tenant-123_registration-456_7890abcd. When support searches for a customer issue, they can find every related log entry instantly.

Audit-friendly logging:

Every significant action should log:

- Actor: Who or what initiated the action (user ID, system job, API key)

- Payload hash: What data was involved (hashed for privacy where needed)

- Outcome: What happened (success, failure, retry)

- Duration: How long it took

This isn't just for debugging. It's for compliance, for audits, for answering "what happened and when?"

Synthetic checks:

Run critical user flows continuously—not just health checks, but actual workflows:

- Log in, view dashboard, submit registration

- Process a test payment

- Query a report

Alert on business failures, not just HTTP 500s. A flow that returns 200 OK but shows wrong data is worse than an obvious error.

Quarantine visibility:

If you have quarantine queues for bad data (you should), expose:

- Current count by error type

- Age of oldest item

- Top 5 error reasons

Alert if quarantine age exceeds threshold. Old items in quarantine mean problems are festering.

Avoid Metric Theater

Some metrics look useful but waste everyone's time:

Too many charts:

If no one owns a chart, delete it. Every metric should have:

- An owner who watches it

- A threshold that triggers action

- A runbook for when the threshold is crossed

Charts without owners become background noise. Noise trains people to ignore dashboards.

Infrastructure-only vanity:

CPU utilization and memory pressure are supporting actors. They matter when they explain business impact. They don't matter on their own.

Tie infrastructure metrics to business outcomes or keep them as low-level alerts, not executive dashboards. "CPU at 80%" means nothing. "CPU at 80% causing registration delays" means something.

Alerts without runbooks:

If there's no documented response to an alert, the alert is noise.

When an alert fires, the on-call engineer should open a runbook and follow steps. If they have to figure out what to do from scratch, either write the runbook or delete the alert.

Case Study: Catching a Silent Regression

In 2017, a code change increased voucher processing latency from 3 seconds to 18 seconds.

Every infrastructure metric looked fine:

- CPU: normal

- Memory: normal

- Error rate: 0%

- Health checks: passing

But the business SLO dashboard showed "vouchers processed in <60s" burning budget faster than normal. Queue age was creeping up. The regression wasn't causing failures—it was causing slowness that would eventually cause failures.

The alert fired when burn rate exceeded 2.0. On-call investigated, found the slow code path, rolled back in 10 minutes.

No customer tickets. No churn. No escalation to executives.

Without business SLOs, that regression would have leaked to customers for days before someone complained loudly enough. With business SLOs, we caught it in an hour.

Building the Right Alerting Culture

Alerts should be:

- Actionable: Someone can do something about it right now

- Owned: A specific person is responsible for responding

- Documented: A runbook explains what to do

- Rare: Alert fatigue kills vigilance

The test: If an alert fires three times and no one takes action, either:

- The threshold is wrong (alert is too sensitive)

- The response is unclear (runbook is missing)

- The alert doesn't matter (delete it)

We ran an "alert hygiene" review quarterly. Every alert that hadn't triggered action in 90 days got reviewed. Most got deleted. The ones that remained were the ones that mattered.

Context → Decision → Outcome → Metric

- Context: 20-year healthcare credentialing platform with enterprise customers who expected reliability, regulated industry with audit requirements, small ops team that couldn't afford alert fatigue.

- Decision: Built reliability measurement around business SLOs, error budgets, and three-layer observability (metrics, logs, traces). Deleted metrics that didn't connect to customer outcomes.

- Outcome: Caught regressions before customer impact. Prioritized reliability work automatically via error budget. Executives stayed informed without dashboard training.

- Metric: Mean time to detect customer-impacting issues dropped from hours to minutes. Alert volume dropped 70% while actionability increased. Zero contract losses attributable to reliability issues in the final 5 years of operation.

Anecdote: The Dashboard No One Watched

In 2015, we had a dashboard called "System Health" with 23 charts. CPU, memory, disk I/O, network throughput, garbage collection, thread pool utilization, and a dozen more.

It was comprehensive. It was also useless.

No one watched it. When incidents happened, engineers didn't look at "System Health." They looked at logs. They looked at error messages. They asked customers what they were seeing.

The dashboard existed because someone had thought "we should monitor these things." No one had asked "what will we do when we see a problem here?"

We deleted 19 of the 23 charts. We replaced them with four business metrics: registration rate, score posting rate, payment success rate, and reconciliation timing.

Those four metrics—plus drill-downs to the underlying system metrics—told us everything we needed. When registration rate dropped, we investigated. When it was fine, we moved on.

The lesson: metrics should answer questions someone is actually asking. If no one is asking, the metric is theater.

Mini Checklist: Reliability Metrics Implementation

- [ ] 3-5 business SLOs defined and measured (not "fast" but "within X seconds")

- [ ] Error budget calculated and burn rate tracked

- [ ] Burn rate threshold triggers reliability work automatically

- [ ] Three signal layers in place: metrics, structured logs, traces

- [ ] Correlation IDs flow from edge through all services

- [ ] Queue age alerts (not just depth)

- [ ] Circuit breaker trip counts tracked over time

- [ ] Executive dashboard with SLOs, incidents, upcoming risks

- [ ] Synthetic checks running critical user flows continuously

- [ ] Every alert has an owner, threshold, and runbook

- [ ] Quarterly alert hygiene review to remove noise